- Hurricane Barry made landfall Saturday morning near Intracoastal City, Louisiana, as a Category 1 storm.

- It has since weakened back to a tropical storm, but heavy rains – between 10 and 20 inches – are expected over the next couple of days.

- A hurricane warning is in effect for much of Louisiana’s coastline, including New Orleans.

- The storm could be the biggest test ever for river levees along the Mississippi. Forecasters warn that the river may reach levels of 19 or 20 feet – the highest since 1950.

- As the planet and its oceans warm because of climate change, hurricanes are likely to get wetter and slower.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Hurricane Barry made landfall near Intracoastal City, Louisiana this morning as a Category 1 storm.

The storm strengthened as it moved toward land, with sustained wind speeds reaching 75 mph. It has since weakened, however, with maximum wind speeds now hovering around 70 mph.

But the winds aren’t the biggest threat: Heavy rains battering coastal Louisiana, with much of the affected area expected to see between 10 and 20 inches of rainfall in the coming days. Some isolated areas could get up to 25 inches.

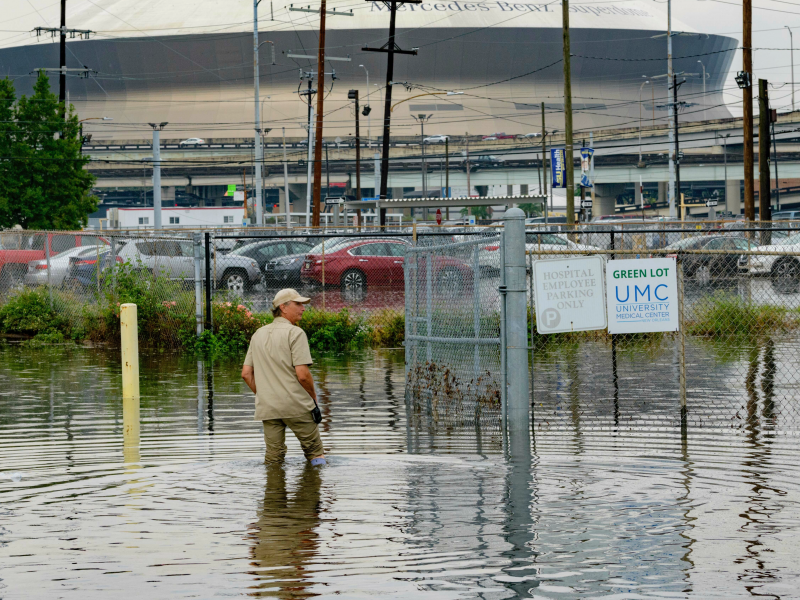

“The primary risk continues to remain heavy rains for the city of New Orleans,” mayor LaToya Cantrell said at a press conference on Saturday morning, adding, “we are not in any way out of the woods.”

Already, water has started to spill over several river levees in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, which sits along the Mississippi River southeast of New Orleans. A mandatory evacuation was issued for the area on Thursday.

A hurricane warning is in effect for the stretch of coast from Intracoastal City to Grand Isle. A storm-surge warning is in effect for the area between Intracoastal City and Biloxi, Mississippi, as well as Lake Pontchartrain. Barry's storm surge - the wall over water above regular tide levels - could reach heights of 6 feet.

Read More: Why hurricanes are getting stronger, slower, and wetter

About 75,000 homes and businesses had lost power in Louisiana as of Saturday morning, according to Nola.com.

Barry is the first hurricane of the 2019 Atlantic season. This is only the third time in 168 years (since researchers started keeping track) that a hurricane has hit the Gulf in July, as meteorologist Eric Holthaus wrote in the New Republic. Typically, August and September are peak hurricane season.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards declared a state of emergency in anticipation of the storm, and US President Donald Trump also declared a state of emergency, authorizing federal agencies to coordinate disaster-relief efforts.

The biggest test of Mississippi River levees since 1927

The storm continues to pose a significant threat to much of New Orleans, since the Mississippi River, which snakes by the city, has been abnormally high since January.

New Orleans has levees in place to keep the river from flooding its banks and swamping nearby neighborhoods, but water has already started to overtop several river levees in Plaquemines Parish. In a press conference on Saturday, officials expressed concern that flooding there could cut off road access for those who haven't yet left.

As rain pummels the New Orleans area, the Mississippi River is expected to crest at a near-record height of 19 or 20 feet on Sunday or Monday - the highest level the Mississippi has reached in the area since at least 1950, according to the NWS. But river levees are only 20 feet high in some places.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina - one of the deadliest storms in US history - killed more than 1,800 people when storm-surge levees along canals in New Orleans failed. The Mississippi River levees, which were built in 1927, stayed intact during that storm. But this week could prove to be their biggest test ever.

"The levees protect the city up to 20 feet, but 19 is close and doesn't include waves splashing up and so on. It's too close for comfort for us," David Ramirez, the chief of water management for the Army Corps of Engineers' New Orleans District, told Slate on Tuesday.

We're likely to see slower and wetter hurricanes

This past year was the hottest on record for Earth's oceans and the fourth warmest for the planet.

As ocean temperatures continue to increase, we'll likely see more coastal flooding due to sea-level rise (since water, like most things, expands when heated) and more severe hurricanes. That's because a hurricane's wind speed is influenced by the temperature of the water below. A 1-degree Fahrenheit rise in ocean temperature can increase a storm's wind speed by 15 to 20 mph, according to research from Yale Climate Connections.

Water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are at near-record levels, Holthaus wrote.

As the planet keeps warming, Earth's atmosphere will be able to hold more moisture. That increases the likelihood of intense rainfall in already wet areas.

What's more, storms are getting more sluggish. Over the past 70 years, the speed of hurricanes and tropical storms has slowed about 10% on average, according to a 2018 study. A slower pace of movement gives a storm more time to lash an area with powerful winds and dump rain, which can exacerbate flood problems.

Hurricane Barry has moved very slowly and is expected to stall over land. A similar sluggishness was also the reason that Hurricane Harvey caused so much damage Houston in 2017.